Voltage, Current, and Resistance - Part 1

Voltage (Symbol: V or E)

- The voltage between two points is the cost in energy (work done) required to move a unit of positive charge from the more negative point (lower potential) to the more positive point (higher potential). Voltage is also called potential difference or electromotive force (EMF).

- The term “voltage” was first coined by Italian scientist Alessandro Volta (18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827). Alessandro Volta was an Italian physicist and chemist who is best known for inventing the electric battery. In 1800, he constructed the voltaic pile, the first chemical battery, which produced a constant electric current.

- Units and Symbols: Voltage is measured in volts, and we use the symbol “V” to represent it.

- The unit of electric potential, the volt, is named in honor of Alessandro Volta for his contributions to the field of electricity.

- The volt is the SI unit of electric potential and electromotive force. It is the potential difference between two points in a conducting wire when one joule of energy is consumed to move one coulomb of charge from one point to the other.

- The coulomb is the unit of electric charge, and it is equal to the charge of 6X1018 electrons, approximately.

- The voltages are usually expressed in

| Teravolts | 1 TV = 1012 V |

| Gigavolts | 1 GV = 109 V |

| Megavolts | 1 MV = 106 V |

| Kilovolts | 1 kV = 103 V |

| Millivolts | 1 mV = 10-3 V |

| Microvolts | 1 µV = 10-6 V |

| Nanovolts | 1 nV = 10-9 V |

| Picovolts | 1 pV = 10-12 V |

| Femtovolts | 1 fV = 10-15 V |

- Analogy: The Hill Analogy

- Polarity:

- Voltage Drop:

- What Voltage Does:

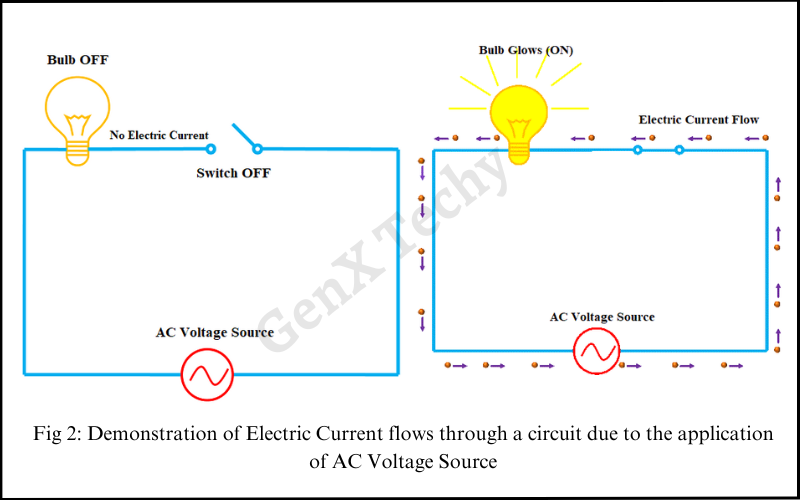

Effect of Voltage application in a Direct Current (DC) Circuit:

In a direct current (DC) circuit, electric current flows from the point of higher electric potential (voltage) to the point of lower electric potential. The movement of electric charge, which constitutes electric current, is driven by the electric field established by the voltage difference in the circuit. The operation is elaborated as follows:- Voltage Source: In a DC circuit, there is typically a voltage source, such as a battery or a DC power supply. The voltage source creates a potential difference between its positive and negative terminals. The positive terminal is at a higher electric potential, and the negative terminal is at a lower electric potential.

Electron Flow:

In a DC circuit, electrons are the charge carriers. Despite the convention of using “conventional current flow” (from positive to negative), electrons actually move from the negative terminal (lower potential) of the voltage source to the positive terminal (higher potential).- Direction of Current: The direction of the current flow is opposite to the movement of electrons. Conventional current is considered to flow from the positive to the negative terminal. This convention simplifies calculations and is widely used in circuit analysis.

- Electric Field: The electric field created by the voltage source exerts a force on the electrons, causing them to move through the circuit. The strength of the electric field is proportional to the voltage.

- Circuit Components: As the electrons move through the circuit, they encounter various circuit components such as resistors, capacitors, and inductors. Each component may affect the flow of electrons differently. For example, resistors impede the flow of electrons, creating a voltage drop across them according to Ohm’s Law (V=I⋅R).

- Complete Circuit: For a continuous flow of current, the circuit must form a complete, closed loop. Electrons move through conductors (wires) from the negative terminal of the voltage source, pass through various components, and return to the positive terminal.

Figure 1 shows the flow of electric current through a circuit due to the DC potential.

As a conclusive statement, voltage is like the “push” or pressure that makes electric charge flow in a circuit. Just as water flows from a higher point to a lower one, electric charge moves from a high-voltage point to a low-voltage point. Understanding voltage is a crucial first step in learning about electricity and how it powers our everyday devices and machines.

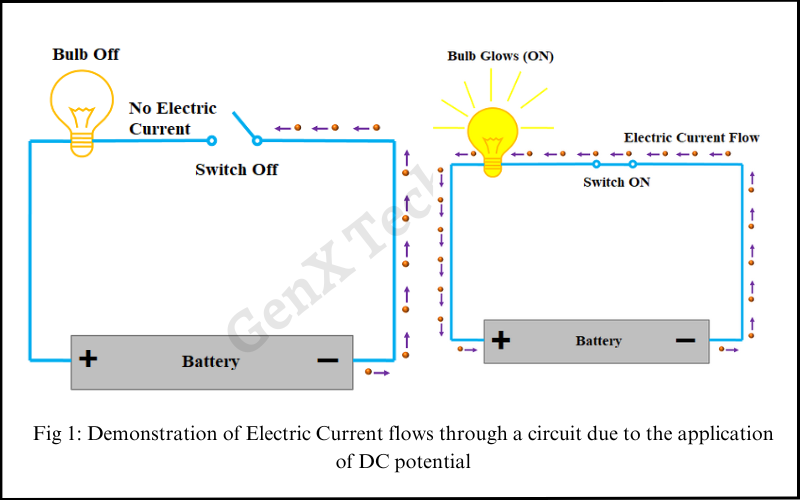

As a conclusive statement, voltage is like the “push” or pressure that makes electric charge flow in a circuit. Just as water flows from a higher point to a lower one, electric charge moves from a high-voltage point to a low-voltage point. Understanding voltage is a crucial first step in learning about electricity and how it powers our everyday devices and machines.Effect of Voltage application in an Alternating Current (AC) Circuit:

In an alternating current (AC) circuit, the voltage continuously changes direction, typically following a sinusoidal waveform. The effect of applying voltage to an AC circuit is fundamental to understanding how electrical systems operate. Here are some key aspects of the effect of voltage application in an AC circuit:Current Flow:- Magnitude: The applied voltage determines the magnitude of the current flowing through the circuit. This relationship is governed by Ohm’s law for AC circuits, where I (current) = V (voltage) / Z (impedance). Impedance is a complex quantity that includes both resistance and reactance (opposition from capacitors and inductors).

- Direction: Unlike in DC circuits where current flows in a single direction, in AC circuits, the direction of the current changes periodically with the applied voltage. This is because the voltage alternates between positive and negative values.

Power Dissipation:

- Heating: The applied voltage contributes to power dissipation in the circuit elements, mainly through heating. This is because resistance in the circuit opposes the flow of current, generating heat. Higher voltage translates to higher power dissipation, which can be a concern for component safety and efficiency.

- Reactive Power: In AC circuits, capacitors and inductors store and release energy, leading to the concept of reactive power. This power doesn’t contribute to useful work but influences the overall power factor and efficiency. The applied voltage plays a role in determining the reactive power flow in the circuit.

Circuit Resonance:

- Frequency: The applied voltage’s frequency can influence the circuit’s behavior in specific situations. For example, at resonant frequencies, capacitors and inductors can cancel out each other’s reactance, leading to a significant increase in current and voltage. This phenomenon can be beneficial for tuning circuits or detrimental if not controlled.

Additional Effects:

- Magnetic Field: In circuits with inductors, the applied voltage induces a changing magnetic field around the inductor. This magnetic field can be utilized for various applications, such as in transformers and motors.

- Electromagnetic Interference: AC circuits can generate electromagnetic interference (EMI) due to their changing currents and voltages. This can be a concern for sensitive electronic equipment and requires proper shielding and grounding techniques.

Figure 2 shows the flow of electric current through a circuit due to an AC Voltage Source.